Real Wilders: How grouse management compares with alternative land uses in delivering for climate and wildlife

Real Wilders: How grouse management compares with alternative land uses in delivering for climate and wildlife

A4 Paperback, 36 pages

Between the 1940s and 1980s, moors that stopped grouse shooting lost 41% of their heather, while moors retaining shooting lost only 24%. For decades, in many parts of the

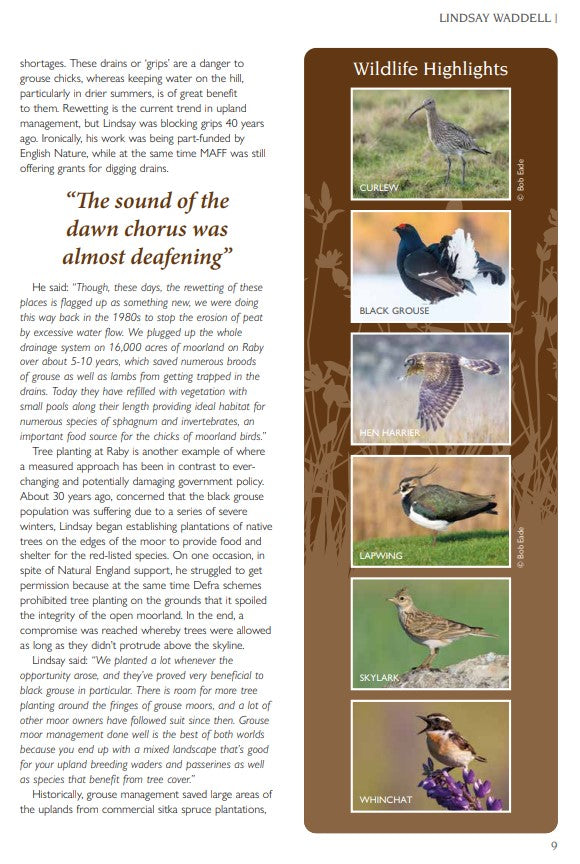

UK uplands the incentive to protect grouse has kept the damaging impacts of commercial forestry or overgrazing at bay and protected some of our rarest species. Like rewilding projects, which manage deer to preserve plantations, grouse managers believe wildlife management is necessary to achieve a balance. These days most grouse managers regard themselves as Working Conservationists who maintain environments at private expense for the wider public to enjoy. They are not set rigidly in their ways, instead they recognise the need to adapt to the latest evidence. They want trees on the fringes as well as dwarf shrubs on the hill, they want to see birds of prey and rare waders as well as grouse and they recognise the value of the range of peat forming plants from bilberry to sphagnum moss.

To give a broader perspective, these case studies include the testimonies of experts outside the grouse management community who recognise its value. Evidence also comes in the form of peer reviewed science and each section has a summary of a relevant GWCT study. More of this kind of research is needed before abandoning management principles which have stood the test of time and protected globally rare heather moorland for decades. As they have in the past, changes in flora and habitat structure through abandonment could have unforeseen negative impacts.

The case studies show what has been lost historically when different elements of grouse management are restricted or absent. This includes the impact of inadequate predation management on the productivity of ground-nesting birds such as capercaillie, the heightened risk of wildfire caused by a reduction or cessation of controlled burning and the devastating effect of both afforestation and intensive agriculture on moorland bird assemblages.

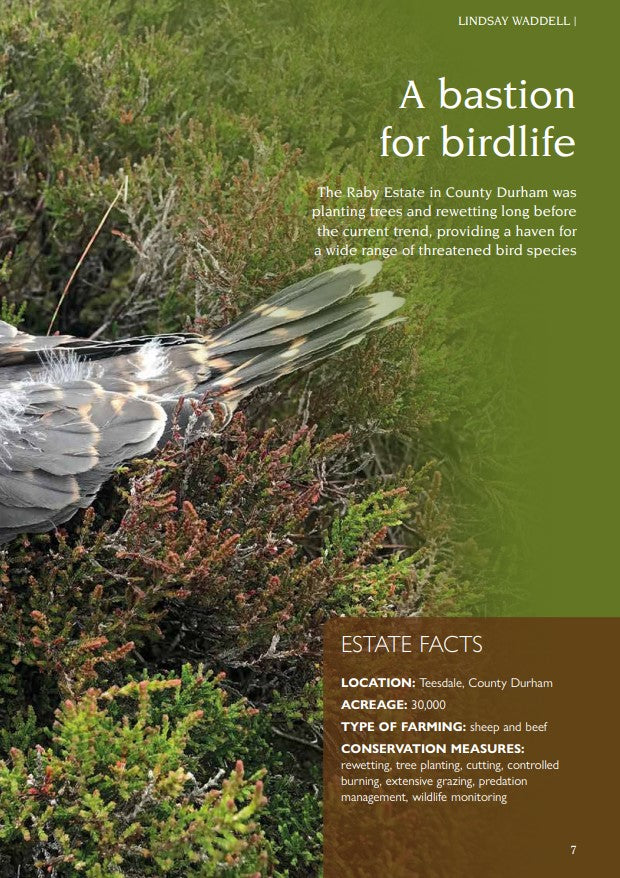

But it’s about the positives, too. Regardless of how you view driven grouse management, it is impossible to deny the extraordinary chorus of breeding birds on a keepered moor in spring that Lindsay Waddell describes hearing for the first time when he came down to the Raby Estate in Country Durham. That sound offers hope for upland peatlands and the endangered birds that depend on them.

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share